The first term has ended and with it comes the continuation of what has gone before. I do not see it as the completion of a phase but rather as the beginning of what is to come. The term has been a time orientation, revisiting and rebeginning, looking at things afresh: all I do seems to ascend in a cycle.

A popup exhibition entitled Virtual Particles has been organised at Camberwell and rather than making a completely new piece, I decided to work on post-truth-hurtling, the kernel of a sketch done earlier in October and take it a little further. With the direction for the mid-term coming into clearer focus through the elaboration of the project proposal, I thought I would try to reflect this in the work. In so doing, I discovered that which I had suspected. That the themes that have emerged, were embedded within the process only to be unveiled by the elaboration of the project proposal. The title tells me everything I need to know; it encodes a number of elements that I had identified in the PP as my way forward for now:

- Mythopoeia – the making of a myth.

- I – that this is only a beginning of a cycle

- post-truth – dealing with current socio-political concerns

- hurtling – my sense of physical things and time being expressed in many different ways, hurtling being one of them

Combining elements of my research in one piece I turned the video sketch into something more layered. The sound track incorporates elements other that Storm Callum . I have begun compiling a fresh archive of sound files and engineered tracks that will serve me in the future. This follows my thoughts in the recent post, Breakthrough from the Simplest Source. It also ties in with what I will talk about in a latter post relevant to my process: that of making a ritual of the recordings.

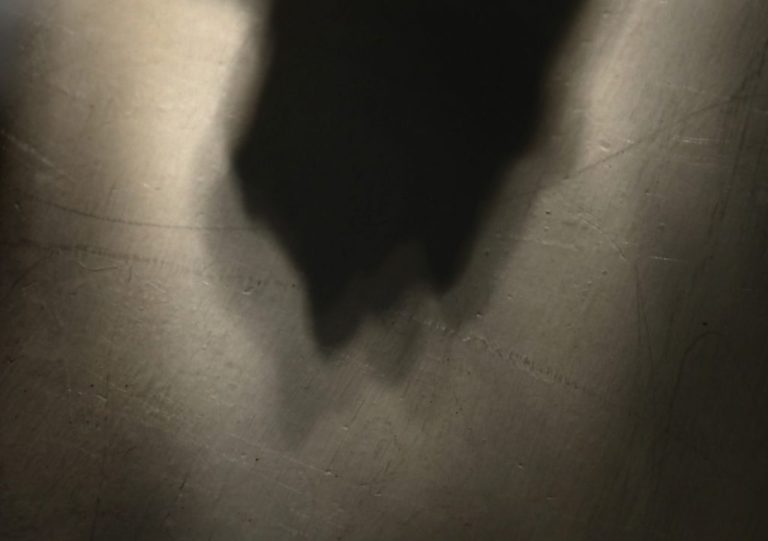

The video incorporates shadows and moving light sources giving which initiates an idea I have had for a while. Animation, of sorts, in an installation that I would grudgingly call for now, Plato’s Cave. My difficulty with this name, although convenient as a temporary place holder, is that Plato’s metaphysical explanation for the illusion of reality was based on people not seeing the true actors and props but only their projections. My idea, on the other hand, is to have three layers of perception in which the actual scenario that creates the illusion is clearly visible and exposed and perhaps even open to interaction.

The text in the video, is a reworking of the original, a selection, distillation, concentration. I aimed at something more incisive and yet ambivalent by taking out the superfluous. As the video unfolds, each word or phrase subsequent to the preceding ones changes the overall inferences. I want the words to remain maleable. Only at the end is the context alluded to.

The elemental characters that went into the making of the video remind me of creation myths in an almost Miltonian sense. I avoid icons of or references to the human world. All that I leave is a sense of imputed volition. It is my way of saying that anthropomorphism is a emergent property of who and what we are, seeing the world in our own image. This is a key element of creation myths in contrast with evolutionary theory. Even in the case of the latter, scientists use teleological language as shortcuts for what would otherwise be very lengthy explanations. A simple example is the phrase, ‘evolving towards’. This assumes a direction or goal, something that is counter to the contingent nature of evolutionary processes; a trap we fall into when describing non goal orientated natural phenomena, because we see things with hind sight as though they were leading to some predetermined goal.

Another notion I wanted to imbue the video with is the sense of things continuing ad infinitum even when one is no longer there: an intimation of eternity. This is something I may work on in the future although it has been done numerous times in different ways. The relentlessness I wanted to give the work is part of its possibly dark interpretation; the soundtrack plays an important role in this. At the end I counterpoise this sense of unrelenting descent with the partial revealing of the context at the end: the open, fresh, natural phenomena used to create spontaneously a dark vision. Sun, wind, tree, clay and water: elements often appearing in creation myths conspiring to weave the ‘horror of creation’, as Ted Hughes might put it, or the dissolution of paradise in a Miltonian world where truth is subverted by lies. 1

- from Crow Alights[↩]