This post was written before and subsequently posted after the previous one. This explains any anachronisms that appear in the text.

In my previous-but-one post, I started by describing how the reconstruction of a narrative by its very nature is at best an approximate endeavour. The description of a past reality in and of itself is in all probability a chimaera made of many parts pieced together as best as one can with the sensory and intellectual tools at one’s disposal. This is the main thrust of Donald Hoffman’s thesis that proposes the impossibility to see the world as it really is. He explains that we experience reality in terms of ‘fitness payoff’ and that this evolutionary pressure has shaped the way we perceive things in terms of what is the best way for us to survive in the world, not the most accurate description of it. So is a narrative a question of convenience and advantage?

Hoffman’s shift in the way the age-old problem of describing reality is approached is another example of how contemporary paradigms are shifting and being replaced at an ever-increasing rate. Thanks to an increasing knowledge base ever more accessible, the ability to bring together disparate areas of interest in one place has stimulated holistic approaches to almost every area of study. Crossing disciplines is essential if new insights are sought.

Alfred Gell’s revision of how artworks might function in society is another example of seeing things differently. His book, Art and Agency singles out precisely the mechanism by which viewers interact with art as though the latter were similar to living beings. Gell sees this in terms of agency, i.e. influencing viewers to behave as though they were engaging with something alive rather than inanimate. An artwork lies within a context, a social environment or art nexus, as van Eck calls it. Van Eck puts it rather well:

[Gell] considers objects of art not in terms of their formal or aesthetic value or appreciation within the culture that produced them. Neither does [he] consider them as signs, visual codes to be deciphered or symbolic communications. Instead, Gell defines art objects in performative terms as systems of actions, intended to change the world rather than encode symbolic propositions about it. Artworks thus considered are the equivalents of persons, more particularly social agents.

Gell identified one mechanism by which viewers can be influenced as technical virtuosity. This presents something made in a way that is hard to comprehend, functioning as a form of ideal or magic. The key is that this thing is to achieve what viewers try to do in other areas. This technical virtuosity can take many forms and is not confined to the skill of carving or painting.

This view of art as a performative agent is at first sight somewhat at odds with Richard Anderson’s view of skilfully encoding culturally significant meaning in a sensuous affecting medium. The skill element is common to both as is the significant meaning. However, in Anderson, the emphasis is placed on encoding meaning, whereas Gell’s hypothesis sees agency as the main function for the artwork.

Anderson in his anthropological idea is trying to bring together very disparate areas of creativity. In his book, Calliope’s Sisters his examples are taken from across very different societies some of which do not recognise the idea of art. Gell’s approach is more art-historical. Both Anderson and Gell are trying to identify art and its function in a way that does not fall into Western artistic paradigms of aesthetics and semiotics. Anderson’s hypothesis focuses on the semiotic content of an art object whereas Gell’s focuses on the mechanism by which an art object exerts influence. Gell’s idea is closer to Bayles and Orlando’s proposition that art changes the world in that he states that the agency of the object [or event] consolidates or reforms a world view in a social setting. This is very much the case in sacred contexts but also in the way art is perceived and responded to in secular white cube spaces to mention just one of many possible examples.

Gell borrows from Peircian semiotics and TAG analysis and replaces terms such as object, meaning, interpreter, sign, signifier etc with words that are more readily applicable to the arts.

- Agency: the power to influence the viewer, this is mediated by the

- Index: the material object that elicits responses

- Prototype: the thing the index is representing.

- Artist: the immediate cause or author of the existence of the index and its properties

- Recipients: those affected by the work or intended to be by the index.

Semiotics, structuralism and post-structuralism originally resided in the literary and anthropological domains. What this does is to slim down the complexities that arise when analysing work in terms of their function in a humanities context. Focus is placed on the visual arts aspect without losing contact with the humanities. Most significantly, the term meaning is exchanged with prototype. This reminds me of the Jungian idea of archetypes. But rather than presenting as a Platonic overarching concept, the prototype can be specific to the index in question.

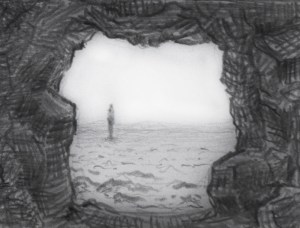

Prototype is an important departure from meaning because it enables the representation of something ineffable. The living presence of the object is enhanced by, in many cases dependent on, its social context. So the art object becomes the explanation of the ineffable rather than ‘the problem to be explained’. 1 Because of the social nexus, in appropriately reinforcing circumstances, the effect becomes proofed against rational explanation. A response mechanism is created that is emotional and volitional rather than rational and cognitive.

These taxonomies are useful when attempting to disentangle relationships and the role of each player in the social nexus in which they are enmeshed. This system of analysis may be a helpful tool in confirming putative or identifying actual causal relationships between the art object its social, anthropological and psychological effects. This form of analysis has been used primarily in art historical context but I can see how I can apply it to tease out aims and objectives from intentions in artistic practice.

I see aims and objectives as analytical descriptions of process. They are the functional and purposeful surface ideas that have to be worked out, arrived at and articulated through cognitive processes. Intentions on the other hand are more deeply rooted. They lie beneath reason, often unrevealed or tacit. To find one’s intention is like holding one’s beating heart. It can be dangerous or bring well being, we often keep intentions well hidden inside the mind; somewhere deep in the brain. Intentions are tinder waiting to be lit. They can give light and warmth or burn everything to ashes.

- Van Eck,[↩]