I have thought a great deal about the role of the sculpture, display and sound in the final show, What is the relationship between these apparently distinct elements and the viewer? This is not primarily about making a multimedia work, it is an exploration of how the stillness of a sculpture, a statue in particular, can be disrupted meaningfully. I see statuary sculptures as passive objects. Their performativity is one of passive resistance to the motility and volitional interaction of the viewer. The viewer can walk around it, touch it, threaten its integrity, choose his or her distance of view, asserting their kinetic capabilities as an expression of their living essence.

A statue is made of inanimate matter yet, as Alfred Gell suggests, can be treated in some ways as though it were living. But this is not living in a biological sense, the living-presence response refers to something that has agency in a social sense. However, a sculpture is not a subject in the ‘conversation’ generated, it is only an object. Its object status distinguishes it from the viewer because of its stillness. This passive silence is underlined by a lack of movement. And even if it were to be animated, this would not change its objecthood. In Ode to a Grecian Urn, Keats’ speaks for the object in a pretence that the object speaks for itself. Clearly the poet’s interpretation, his apparent conversation is one way as though it were a dialogue. The virtue of the vase lies in its silence, allowing the poet to exercise a dominion over the object.

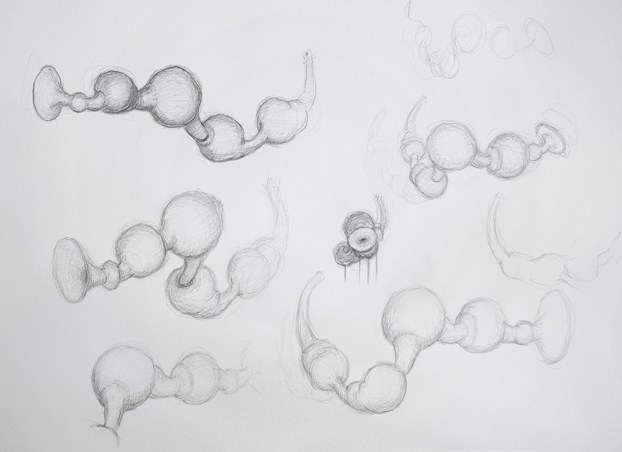

David Getsy explores this power play between object and subject in his essay, Acts of Stillness: Statues, Performativity, and Passive Resistance. A statue’s ambivalence with respect to its position vis a viz the viewer is also its strength. As a passive object, a statue is subject to the actions of the viewer(s). However, this very inability of a statue to be physically volitional towards a viewer alters the latter’s behaviour through its passive resistance. It exerts a form of power that is used in monuments, sacred art and gallery based works. I explored this notion in Chaos Contained. The works were displayed openly in museum and gallery settings, vulnerable in their fragility and delicacy of form. This created a tension between the act of looking and the desire to touch whilst offering jeopardy in the very act of viewing. This altered the viewers’ behaviours, largely from being dominantly motile to cautious and circumspect. The works were approached often with trepidation which was accentuated by the deliberately aesthetic structures which proclaimed their brittle integrity. Although the works in Chaos Contained exerted power and agency by virtue of their formal and material properties, they were not subjects in a conversation. I was aware of their agency, they were conceived as such, but I saw them as objects and referred to them as objects of the mind. In these conversations, I remained largely hidden behind the act of completion of the works. This view of the art object does not discount performativity of the works themselves, just as listening to a recording does not alter the fact that what one is listening to is an acoustic object in a one-way conversation at the time of listening. With a static statue, the performance is its stillness, its silence, its resistance by virtue of its non-motility.

Gell’s view of the art object as a social agent is all well and good, but a sculpture cannot speak for itself. Meaning and the social nexus can only come as a function of the nexus formed by the recipient, the context, prototype and index, to use Gell’s terminology. But is that all? I think not, what Gell does not take into account is the agency of the artist, who is hidden in all probability. (However, I must say at this point that the nexus can become largely distorted in contemporary contexts as to whether the artist is known, unknown, famous or notorious.) Perhaps this omission is on account of Gell’s anthropological standpoint. The artist is reduced to artisan level, interpreting the idea being represented, with skill and according to the current view of things. I think that the artist is far more than an artisan but not because the work cannot come about without the artist’s action. A work of art is in my view, not only a reflection of the social setting but has a point of poietic origin within the artist’s inner self. There is a danger in extrapolating Gell’s anthropological work, set in well established, relatively stable social contexts, where tradition dictates the artisan’s work. This is not the case in Western tradition of art which despite the constraints of contemporary established cannons, has always displayed a great capacity for experimentation and innovative change.

This complex relationship between artwork, context and viewer is often reduced to the metaphor of conversation. But there is more going on here than an exchange that alters viewpoints. An artwork does not just have agency on a rational or dialectic level, it affects the emotions in some way. One could argue that this is its prime function, to affect the recipient beyond rhetoric. This is not so much a conversation as an experience that is processed more rationally after the encounter.

Where does this take me in relation to the project proposal? The works I am currently engaged with could be left as still representations of an idea. But I am also working with sound and display. The aim is to break through the silence, the stillness of the statue. Rather than exert its effect passively, dependent on how the viewer decides to approach it, I am looking at ways of controlling the motility of the viewer in various ways. Khadija von Zinnenberg Carroll sees the vitrine as a performative element in its own right. It only takes a little observation to see how a vitrine can affect the behaviour of visitors in a museum. Their physicality changes with respect to other forms of display. A vitrine not only alters the way an artwork is viewed but also how it is experienced. A vitrine creates a barrier that frustrates the impulse to touch and approach closely paradoxically forcing the viewer to come as close as they can. This is something that von Zinnenberg plays with, in the video, accompanying her essay Vitrinenedenken: Vectors Between Subject and Object. The vitrine becomes, not just a means to display, but an object in itself, an interactive participant in the work with its own agency.

I am using a vitrine in one of the works, I aim to create that barrier between the work and the viewer as the recipient is distanced from the subject matter in time. This transparent tegument is, however, pierced allowing sound narratives to transpire across the membrane. The permeability is designed to draw the viewer closer creating a sort of intimacy, scent the inner world and lower the resistance to engage. The stillness of the statue is broken yet it remains non-motile. A painting’s frame circumscribes the limits of its world, untouchable yet tangible, that thingliness that forms an aura. The three-dimensional frame alters the statue to something removed, as are the notions (prototypes) indexed by it, and its passivity and aloofness is disrupted by the sound. This idea has arisen out of consideration for the subject matter: the unreachability of the past, contingency and the vulnerability of meaning in language through interpretation, a form of Babel. Yet, the devices I mention here stand alone as conceptual works in themselves, as demonstrations of the process.

I also look to use sound as an invisible ‘vitrine’ with its own performativity. This time the membrane is not rendered permeable by means of piercing a physical integument but by creating a kinetic relationship with the sculpture Again the viewer can control and is controlled by their kinetics and those of the sound, choreographing movements in a different way. In this case, the acoustic vibrations ‘encase’ the sculpture as an electron cloud might enclose the nucleus of its atom. It affects the properties with a charge of energy, indeterminate and diffuse.

Both these works take from the notion of the statue as a vessel with an internal and external world. The integument created by the modes of display I am planning is to be permeable with elements of distal-proximal engagements.